Welcome to this week’s edition of TOPICAL WEDNESDAY. This time, we dive into the looming face-off between Tata Sons and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). What started as a regulatory framework for NBFCs has snowballed into a high-stakes standoff: should India’s most iconic holding company list publicly for the first time in its 150-year history, or can it find a way to stay private?

From regulatory pressure to family trust control, from SP Group tensions to investor expectations, this September deadline could redefine not just Tata Sons’ future but also how corporate governance and regulatory power play out in India. The question is simple, but the answer will shape the country’s business landscape for decades :Will Tata Sons finally go public or fight to stay in the shadows?

Few business stories in India bring together history, regulation, family dynamics, and investor interest quite like this one. At the center is Tata Sons the holding company that anchors the Tata empire – and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). By the end of September 2025, Tata Sons faces a major decision: whether to go public for the first time in its 150-year history, or find a way to avoid listing altogether.

The outcome will not only affect Tata Sons and its shareholders. It could also reshape the balance of power between India’s regulators and its most influential corporate houses.

How the September showdown started

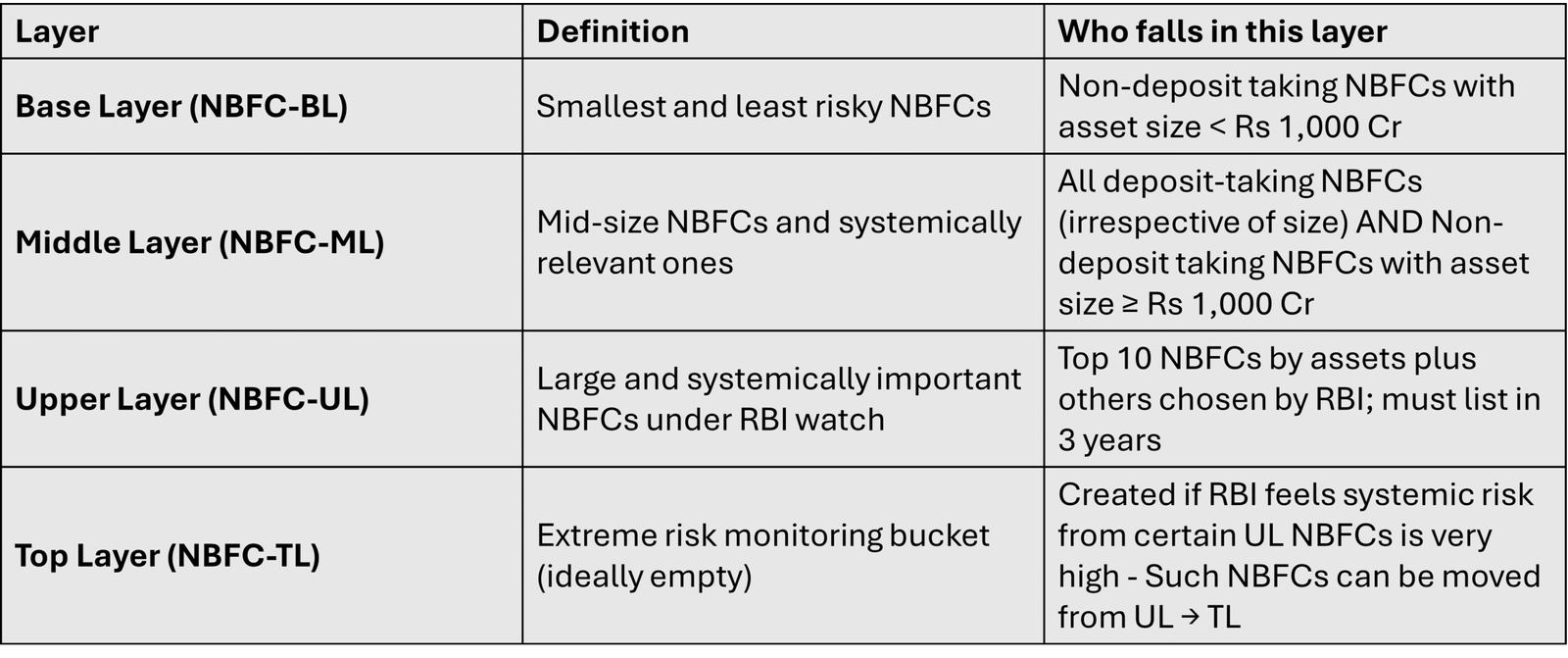

In 2021, the RBI introduced Scale-Based Regulation for non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). The logic was simple: the bigger and more important you are to the financial system, the stricter the rules. At the top sits the Upper Layer (NBFC-UL), which carries heavier compliance standards including a rule that unlisted UL entities must list within three years.

Tata Sons was placed in this category in September 2022, starting a three-year countdown that ends in September 2025. Others like LIC Housing Finance Limited, Bajaj Finance Limited, Aditya Birla Finance Limited etc., were also placed in this category.

For the RBI, this is about transparency and discipline for large financial groups. For Tata Sons, it is about avoiding the glare of public scrutiny. That difference sets the stage for the current standoff.

(Source: RBI, Bastion Research)

RBI’s demand vs Tata Sons’ resistance

RBI’s view: If a company is systemically important, both regulators and investors deserve a full picture of its risks and operations. Listing forces that disclosure.

Tata Sons’ view: A public listing creates two major challenges:

- Loss of flexibility – A listing would move Tata Sons from a trust-controlled model into the strict world of SEBI regulations. This would mean quarterly earnings reports, independent directors on the board, and full disclosure of major decisions like acquisitions and dividends. For the Tata Trusts, which currently exercise near-total control, this loss of privacy and independence is highly undesirable.

Examples of how experiments have carried volatility in the past:

Tata Digital / Neu: losses while scaling BigBasket, 1mg and the Neu app; FY25 net loss was about Rs 828 Cr. As a listed parent, this would draw constant quarter-to-quarter scrutiny.

Tata Electronics: Rapid scale in iPhone assembly with continuing heavy capex and integrations such as the Pegatron India deal. Even with losses narrowing, investors would scrutinize yields, ramp curves, and working-capital swings at the parent level. Tata Medical & Diagnostics: A young platform that has changed course and continues to post operating losses, relying on parent support. Public markets would probe strategy shifts and cash burn every quarter.

- Valuation discount – Holding companies across the world face a “conglomerate discount.” Instead of being valued at the total worth of their subsidiaries, markets typically apply a 30-50% discount because of debt layers, related-party transactions, and opaque structures. For Tata Sons, which owns valuable stakes in TCS, Titan, Tata Motors and others, this could mean its market value would fall far short of the combined value of its holdings.

Timeline of key events

- Sep 2022: RBI identifies Tata Sons as an NBFC-UL, triggering the three-year clock. For investors, this was the first sign that a Tata Sons listing could be forced.

- FY23–FY24: Tata Sons repays over ₹20,000 crore in debt, sharply reducing its use of public funds. This raised debate among investors: with little outside borrowing, does the listing rule still apply as strongly?

- Aug 2024: Tata Sons applies to surrender its NBFC/Core Investment Company license. The RBI continues to list it as UL “without prejudice” while reviewing. To investors, this looked like an attempt to escape the listing requirement altogether.

- Jul–Aug 2025: Tata Trusts formally state their preference to stay private. At the same time, reports emerge of renewed exit talks with the SP Group (which holds ~18%). This signalled to investors that the group might prefer a private settlement over a public listing.

- Late Sep 2025: With the deadline days away, no draft prospectus has been filed, and no bankers have been appointed. For the market, this silence is telling: will the RBI force the issue, or will Tata Sons manage to avoid it?

There are four broad possibilities:

Possible escape routes for Tata Sons

- Exemption or de-registration: If the RBI accepts Tata Sons’ request to surrender its NBFC licence, the listing requirement disappears. Investors lose their chance at owning the parent, while Tata Trusts keep control.

- Court challenge: Tata Sons could argue in court that the rule is being applied retrospectively. This could delay the process for years. Investors would face continued uncertainty, with no clear path to access or disclosures.

- Restructuring: Tata Sons could shift assets or change how subsidiaries are held to reduce its NBFC exposure. This would not create a direct listing but could bring more clarity through its listed companies.

- Forced listing: If the RBI rejects all other options, Tata Sons may have to go public via IPO or offer-for-sale. This would give investors rare access to the group’s parent, but at the cost of a likely holding-company discount.

For investors, the outcomes look very different in each case ranging from being shut out completely, to finally getting a rare chance to invest directly in the parent of India’s most famous business group., convenience, and cost. It offered banks a one-stop solution, while operators benefited from higher footfall. But because operators ultimately owned the lounges and customer experience, they could cut out the middleman for higher margins or control. That is exactly what played out in 2025.

Shareholder battle: Tata Trusts vs SP Group

This standoff is also shaped by shareholder tensions inside Tata Sons, which have deep historical roots.

- Tata Trusts & Other group companies (~82%): The charitable trusts led historically by J.R.D. Tata and later Ratan Tata have always prioritized control and long-term stability. They view their stake as custodial rather than financial and have consistently tried to keep decision-making private and insulated from market pressures.

- Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group (~18%): The SP Group first acquired its stake in Tata Sons in the 1960s through construction magnate Pallonji Mistry. Over time, it became the largest minority shareholder. The relationship, though stable for decades, became more complex in the modern era. In 2012, Cyrus Mistry, son of Pallonji Mistry, was appointed chairman of Tata Sons — the first non-Tata to lead the group. His appointment was seen as a bridge between the Trusts and the SP family. However, differences in strategy and governance philosophy soon surfaced. In October 2016, the Tata Sons board abruptly removed Cyrus Mistry as chairman, citing a loss of confidence. The ouster led to one of India’s most high-profile corporate battles, with the matter reaching the National Company Law Tribunal and eventually the Supreme Court, which ruled in favour of Tata Sons in 2021.

The fallout deepened mistrust. In 2020, the SP Group sought to exit its holding, valuing it at more than ₹1.75 lakh crore, though no deal was finalised. For the SP Group, the stake is primarily financial, and monetisation has long been a priority. For Tata Trusts, retaining control and shielding the parent from external influence has remained paramount.

Now in 2025, this divide is once again central. A listing would offer the SP Group an open-market exit, while Tata Trusts fear dilution of control. If Tata Sons avoids listing, a negotiated buyout or asset swap with SP may be inevitable. For investors, this internal tug-of-war is just as significant as the RBI’s stance, because it will ultimately decide whether public markets ever gain access to Tata Sons.

Tata Capital IPO: A sharp contrast

While Tata Sons resists, Tata Capital, also an NBFC, is preparing for a ₹15,000–17,000 crore IPO in October 2025. It will be the group’s largest listing so far.

Investor takeaways

If Tata Sons lists:

- Investors finally get direct exposure to the parent of India’s largest business group.

- But they must accept a holding-company discount, paying for complexity rather than clarity.

If Tata Sons avoids listing:

- The SP Group might still get an exit, but public investors will lose access to the parent entity.

- The RBI’s credibility would be tested, and investor attention would remain on listed subsidiaries like TCS, Titan, Tata Motors, and soon Tata Capital.

Either way, the outcome will influence how investors judge India’s regulatory consistency and corporate governance standards.

Lessons from peers

- Some NBFCs such as Tata Capital and HDB Financial Services (HDFC group) have chosen to fast-track IPOs to meet the RBI’s Upper Layer listing requirement, ensuring compliance within the three-year deadline.

- Others, like LIC Housing Finance merging with IDBI’s lending arm or Shriram Group’s NBFC consolidation, have restructured or merged with already listed entities to comply indirectly and reduce regulatory exposure.

What to track in the weeks ahead

In the weeks ahead, all eyes will be on the RBI’s decision regarding Tata Sons’ NBFC license. That ruling alone could settle the question. Investors will also look for any sudden signs of listing preparation – such as banker appointments or draft filings – that might suggest a reluctant IPO. Parallel negotiations with the SP Group could point to a private settlement instead. At the same time, the reception to. Finally, SEBI’s stance on phased public float norms for very large companies will influence how any potential listing is structured.

Together, these factors will determine not only Tata Sons’ immediate future but also set benchmarks for governance across corporate India.

Closing thoughts

September is more than just a deadline. It is a defining moment. Either Tata Sons steps into the public market for the first time, or it finds a way to resist, testing the strength of India’s regulators.

For investors, the decision will offer lessons that go beyond Tata Sons it will show how India is rewriting the rules of corporate governance, and who truly has the final say.

We’d also love to hear your thoughts and feedback on X. Connect with us there at @bastionresearch.

Happy Investing!!!

Disclaimer: This newsletter is for educational purposes only and is not intended to provide any kind of investment advice. Please conduct your own research and consult your financial advisor before making any investment decisions based on the information shared in this newsletter.

😂Meme of the Week🤣

Follow us

If you are a diligent investor, you would not want to miss checking out our research platform, where we share insightful research on companies regularly. Gain access to our sample research by clicking on the button below.