Welcome to this week’s edition of TOPICAL WEDNESDAY. This week, we look at the new Income Tax Bill which brings a major change to the taxation system.

Every few decades a country rewrites the rules of money. India just did. The Income-Tax Act, 2025 replaces a 60‑year‑old code with something clearer, more digital, and harder to game.

It is notified and takes effect from April 1, 2026. The government’s stated aim is simple: modern drafting, fewer disputes, and a system that matches how we actually earn and record income today.

What is the Income Tax Act, 2025

India’s modernised direct tax law that replaces the 1961 Act-rewritten for clarity, a single Tax Year, digital‑first compliance, and explicit rules for digital assets.

Parliament passed the revised bill with commencement set for April 1, 2026. This is the biggest rewrite since 1961. The Ministry frames it as a structural clean‑up rather than a rate shock.

Here are the Major Changes

1) Structure and simplicity

- 1961 Act: Over 800 sections, complex wording, with multiple amendments layered over decades. For example, even a simple provision like tax deductions for investments (80C) would reference multiple subsections and provisos that left most taxpayers reliant on consultants. The length and complexity also made litigation common, as interpretations varied across tribunals and courts.

- 2025 Act: Trimmed to 536 sections, spread across 23 chapters and 16 schedules—reorganized and simplified. The language is plainer, overlapping provisions have been merged, and related topics are grouped logically. For instance, all individual deductions are placed together in one schedule rather than scattered across the code. This structural clarity makes it easier for an average taxpayer or investor to locate the applicable rules without needing legal decoding.

Well, CA students should be relived, less provisions and sections to remember.

2) A single Tax Year

- 1961 Act: “Previous Year” and “Assessment Year” caused confusion. For instance, income earned between April 2022 and March 2023 was called the ‘Previous Year’, but you filed your return in July 2023 under the ‘Assessment Year’ 2023-24. This dual terminology tripped up many taxpayers who struggled to match which income belonged to which filing cycle.

- 2025 Act: Unified Tax Year, aligning reporting and payment. Under the new system, the income earned between April 2025 and March 2026 will simply be called ‘Tax Year 2025-26’. This makes reporting straightforward and removes the mental juggling between previous and assessment years.

3) Higher Exemption Limit

The new Act retains the ₹12 lakh basic exemption, introduced in Budget 2025. This continues to support middle-income earners by ensuring that individuals with annual income up to ₹12 lakh pay zero tax.

For example, if someone earns ₹11.5 lakh in FY26, they will not owe any tax, whereas under the old system with a much lower exemption threshold, a portion of this income would have been taxed. On the other hand, someone earning ₹15 lakh will only be taxed on the total income earned.

This higher base frees disposable income for consumption and investment, while making tax planning less dependent on complicated deductions.

4) Cryptos, NFTs now part of the act

The Act explicitly brings crypto, NFTs, and other virtual digital assets under the definition of income, ensuring tighter compliance.

Under the old 1961 Act, taxation of crypto was vague and inconsistent, profits from crypto trades were often contested as either business income, capital gains, or even left unreported. For example, if you sold Bitcoin in 2022, some people declared it as speculative business income while others ignored it due to lack of clarity.

The 2025 Act removes this ambiguity: if an investor sells Bitcoin or an NFT for a profit, that gain will now be reported as taxable income under the new law (taxed at 30% flat), similar to gains from selling shares. This change aims to plug tax leakages from the fast-growing digital asset space.

One important point is that gains from VDAs cannot be set off against losses from VDAs, meaning if you make a profit on Bitcoin in one trade, but a loss on another trade, the VDA gain still gets taxed in full at 30%. This is a bit of a bummer for investors, but it clearly signals the government’s stance of discouraging speculative exposure to digital assets.

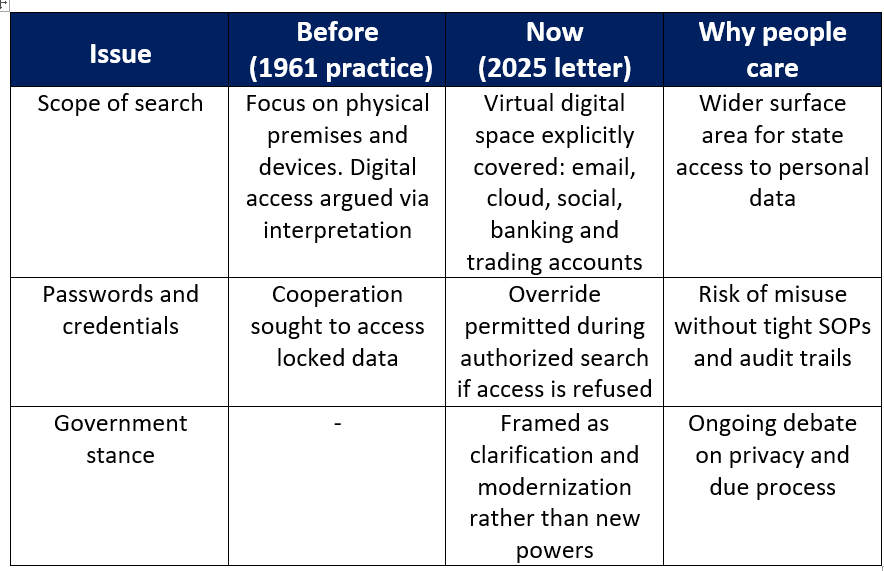

5) Your Digital footprint can now be accessed

Tax authorities can access emails, trading accounts, social media, and cloud storage during searches. The new powers extend scrutiny into the digital footprint, meaning if an investor hides gains in an overseas trading app, stores crypto keys on Google Drive, or even discusses undeclared income over email, these can now be examined. Transparency and clean audit trails are more important than ever, as digital forensics will play a direct role in tax enforcement.

6) Capital Gain Relief

- Old: Long-term capital losses (LTCL) could only be set off against LTCG. For example, if you lost ₹2 lakh in shares held for more than a year in FY23 but had ₹2 lakh profit from short-term stock trades, you could not adjust one against the other. The LTCL simply carried forward, often unused.

- New: One-time relief, Long Term capital losses accumulated up to March 31, 2026 can be set off against short-term capital gains (STCG) in FY26. For instance, if you are carrying ₹5 lakh in Long term capita loss from past years and make a ₹7 lakh profit from short-term trades in FY26, you can offset the entire loss and only pay tax on the net ₹2 lakh. This window is particularly relevant for investors who want to clean up old portfolios and unlock tax efficiency.

7) Late Filing? No Problem, you will get your refund

- Refunds allowed even if returns are filed late (in good faith). For example, if a taxpayer files their FY26 return a few weeks after the due date but genuinely missed it without malice, they can still claim a refund of excess TDS. Under the old regime, such refunds were often lost despite genuine delay.

- Notices from the tax department are now mandatory before action. This means if the tax department wants to re-open an assessment or question a claim, they must first issue a formal notice. For instance, if your refund claim is flagged, you will get a prior intimation rather than an abrupt adjustment, giving you a chance to respond and clarify.

8) Faceless, Digital First Compliance

Expands faceless assessments, reducing scope for harassment but demanding precise digital reconciliations between broker data, AIS, and ITR.

Under the old system, assessments often meant in-person visits and subjective questioning by officials.

Now the process is entirely electronic—returns are flagged by algorithms, and queries are raised online. Similarly, dividend income or interest reflected in the AIS but missing in your filing will be questioned digitally. This reduces discretionary power of officers but makes accurate digital records and reconciliations absolutely critical.

Why did India need a new bill?

India needed a new bill because the 1961 Act had swollen, over six decades and 700+ operative provisions into a contradictory, hard-to-navigate maze.

The 2025 rewrite tackles this with clarity over clutter (plain drafting, cleaner sequencing, tighter definitions), is digital by design (faceless assessments and e-procedures built in), and catches up with the economy by baking digital income, platforms, and VDAs into the core law. It restores operational sanity by replacing the confusing previous-year/assessment-year split with a single Tax Year.

And it also nudges India toward global best practice—closer to the UK/Australia model—while Singapore remains the simplicity benchmark.

Areas of Criticism

Critics largely applaud the cleaner drafting but worry the substance hasn’t shifted:

The Act widens digital search powers, explicitly covering cloud, email, bank/trading accounts and even allowing password overrides, raising privacy and overreach concerns

it keeps the hard line on crypto (no loss set-off, punitive economics), which may continue to push serious trading offshore and it’s seen as structural streamlining rather than substantive reform, with headings, language, and placement of provisions tidied up but little change to the underlying tax logic, definitions, or real-world compliance burden.

Impacts on Different sectors

1) Insurance, Health Insurance & Financial Products

Tax breaks under 80C (life/ULIPs) and 80D (health premiums) historically drove a large share of policy sales. With the new regime offering a ₹12 lakh exemption and fewer taxpayers needing deductions, that incentive weakens.

- Life Insurance: Pure protection (term plans) remains essential, but “investment-linked” products lose appeal.

- Health Insurance: Demand stays intact due to rising medical costs, but less tied to deductions.

- Impact: Traditional insurers and brokers that relied on the “save tax” pitch may see slower growth, while mutual funds and NPS benefit as investors redirect savings into return-driven instruments.

2) Real Estate & Housing Finance

Under 1961 Act, Tax deductions on home loan interest and principal (80C + 24B) were strong motivators for buying property.

However in the new regime’s ₹12 lakh exemption, fewer taxpayers will need these deductions—weakening the “tax benefit” narrative and shifting demand toward lifestyle-driven purchases.

As a result, NBFCs and HFCs like HDFC Ltd. and LIC Housing Finance may see subtle behavioral changes in housing demand, with growth less dependent on tax incentives.

3) Digital Assets & Crypto Ecosystem

Gains from crypto, NFTs, and other VDAs must now be fully disclosed and cannot be set off against other losses, which discourages speculative trading and hurts domestic exchanges like CoinDCX and WazirX.

In the long run, this push for stricter compliance may drive investors away from unregulated digital assets and toward regulated investment products.

4) Mutual Funds & Wealth Platforms

With the new regime, tax-saving compulsions like ELSS fade, and investors are more likely to channel money into SIPs, ETFs, and index funds for actual returns rather than deductions.

This shift benefits digital brokers and wealth platforms such as Zerodha, Groww, and Paytm Money, which stand to capture rising voluntary, transparent savings flows.

5) Retail Consumption & Discretionary Spending

With a ₹12 lakh exemption freeing more disposable income, middle-class households will have extra cash that no longer needs to be locked into tax-saving products.

This is positive for FMCG, retail, travel, and consumer durables, where spending is likely to rise as savings shift into consumption.

Closing Thoughts

The Income Tax Bill 2025 quietly rewrites the playbook for Indian investors. By removing the crutch of tax-linked products, it puts the spotlight back on fundamentals-risk, return, and liquidity.

The Income Tax Bill 2025 quietly rewrites the playbook for Indian investors. By removing the crutch of tax-linked products, it puts the spotlight back on fundamentals-risk, return, and liquidity.

Over time, this can foster healthier portfolios built on conviction rather than compliance, with SIPs, ETFs, and direct equity gaining ground over hurried year-end buys.

While the discipline of tax-saving once shaped habits, the next chapter may see investor maturity shaped by market cycles, product innovation, and financial literacy. In the coming years, portfolios are likely to look leaner, more transparent, and more global in flavor, less about deductions, more about decisions.

We’d also love to hear your thoughts and feedback on X. Connect with us there at @bastionresearch.

Happy Investing!!!

Disclaimer: This newsletter is for educational purposes only and is not intended to provide any kind of investment advice. Please conduct your own research and consult your financial advisor before making any investment decisions based on the information shared in this newsletter.

😂Meme of the Week🤣

Follow us

If you are a diligent investor, you would not want to miss checking out our research platform, where we share insightful research on companies regularly. Gain access to our sample research by clicking on the button below.